Camille H Quan Soon, Marlon M Mencia

Department of Clinical Surgical Sciences, Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Camille H Quan Soon

Department of Clinical Surgical Sciences, Faculty of Medical Sciences,

The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

[email protected]

DOI:

DOAJ: dfd85fa2fb8d402fa8b804f0a9c4b6ad

Copyright: This is an open-access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

©2023 The Authors. Caribbean Medical Journal published by Trinidad & Tobago Medical Association.

ABSTRACT

Objective

To determine undergraduate medical students’ attitudes to e-learning of orthopaedics implemented due to lockdowns resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Methods

An anonymised online survey was distributed to all final year medical students at The University of the West Indies (UWI) in Trinidad after completing the distance-learning module of the Trauma and Orthopaedics clerkship.

Results

Sixty-seven completed questionnaires were analysed, response rate 32.7% (67/205). There were 37 female students (55.2%), with a mean age of 24.7 years (range 22 – 44 years, SD 3.13). Although all students were familiar with e-learning platforms, only 44.8% had previously used e-learning resources. Minimising exposure to Covid-19 was identified as the most significant benefit of e-learning (17.9%, n=12). Other advantages included being able to work at their own pace and style of learning (11.9%, n=8), ease of access to teaching material (10.5%, n=7), and equity of resources (10.5%, n=7). The greatest disadvantages to e-learning were loss of direct interaction with patients (26.9%, n=18) and lack of privacy at home (19.4%, n=13). Most students (71.6%, n=48) were satisfied with e-learning; however, the majority (67.2%, n=45) felt that this method could not singularly achieve clinical competence.

Conclusion

E-learning was widely accepted by students as an effective method of curriculum delivery but insufficient for mastering the clinical skills required to be a competent doctor. The use of blended programmes which combine e-learning and traditional bedside teaching should be encouraged in the post-pandemic future.

Keywords: Caribbean, e-learning, Covid-19, orthopaedics, medical education

INTRODUCTION

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic, resulting in worldwide changes to medical education. There was an immediate termination of in-person clinical experience with the cancellation of traditional classroom teaching, clerkships, and reduction in elective surgery. 1,2 The lost opportunity for skill acquisition, personal development and its effects on a medical student’s career remain largely unknown.1,3 In Trinidad and Tobago, The University of the West Indies (UWI) ordered an indefinite suspension of all face-to-face classes at the St. Augustine campus. To continue tuition of medical students, and to facilitate their timely graduation and integration into the healthcare workforce, the existing curriculum had to be quickly transformed with the addition of an e-learning component.

The pandemic has resulted in e-learning being widely adopted in medical education with the promise of greater effectiveness and student satisfaction. A survey of Scottish orthopaedic residents found that e-learning resulted in an overall increase in teaching during the pandemic.4 These findings are contrary to a survey of orthopaedic residents in South Korea.5 Most studies report that learners are generally satisfied with e-learning, citing convenience, flexibility of time and reduced travelling as benefits.4, 6-8 Distractions at home and poor connectivity were reported as disadvantages to e-learning.9 Although the pandemic resulted in increased use of e-learning, in one study residents were less satisfied with e-learning compared to traditional teaching methods. 5

The effects of e-learning and its acceptability to medical students during the pandemic remains both understudied and controversial. Enjoyment and satisfaction of medical students with e-learning has been linked to a positive effect on knowledge, skill acquisition and retention. 8, 10 Similarly, relevant medical education resources are important in the training of medical students to be competent doctors. 11 It is therefore important to evaluate major changes to the educational curricula to determine satisfaction and relevance, as this may influence the quality of the doctor produced. The aim of this study was to determine the opinions and attitudes of final year medical students to the e-learning module of the Orthopaedics curriculum. This study therefore seeks to add to the literature on e-learning during the pandemic by focusing on students’ perceptions.

METHODS

The class of final year medical students (Class of 2020) consisting of 205 students were divided into six groups each having between 32 to 37 students. All clinical clerkships were split into isolated halves, the first half of which was strictly online, followed by the traditional hospital-based face-to-face teaching when lockdowns ended. The e-learning component of the clerkship was delivered over two weeks to each of the 6 groups. Online teaching was delivered using both synchronous and asynchronous methods. Synchronous lectures usually lasted for 60 minutes and utilised Zoom® because of its convenience and robust platform. Students accessed asynchronous resources including slide presentations and videos, on the university’s online learning management system. All students completed the e-learning module of the Orthopaedics clerkship between June and October 2020.

After all groups had completed the online teaching, the students were emailed an invitation to complete our survey. The survey could be completed on mobile devices and personal computers using the browser-based REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). The students’ internet protocol (IP) addresses were used to ensure that duplicate submission by the same student was not possible. Students were advised that participation was voluntary, anonymous and the data collected would be used for research. Students who did not respond to the initial email were sent one reminder and the survey closed one month after it became available.

The cross-sectional survey was conducted using a 13-item questionnaire which was devised by the authors based on previously published studies [7,9,12]. It was pilot-tested to ensure clarity and validity. Questions explored several domains including demographics, opinions towards online teaching and learning, anxiety levels, concerns about privacy and overall satisfaction. Students’ self-perception of anxiety caused by the pandemic was evaluated using 4 point Likert scale as follows: (No anxiety, 0; mild anxiety, 1; moderate anxiety, 2; severe anxiety, 3) and converted to a numerical score.

Data were transferred into MS Excel® and analysed using Analyse-it for Microsoft Excel 5.40 (Analyse-it Software Ltd) ®. Descriptive statistics were used to present the demographic data and categorical variables reported using frequencies and percentages. The results were presented using the mean ± standard deviation values. Chi-squared test was used to compare differences in responses between sex. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Campus Research Ethics Committee, Graduate Studies and Research, The University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, Trinidad (CREC-SA.0511/09/2020). Our study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations concerning surveys. All students gave written informed consent to participate in the study. The consent form was part of the online survey.

RESULTS

One hundred students (48.8%) responded to our invitation and visited the website. There were 5 read-only site visits and 28 incomplete questionnaires, leaving 67 fully completed questionnaires that were used for further analysis. There were 37 female respondents (55.2%), with a mean age of 24.7 years (range 22 – 44 years, SD 3.13). All students reported prior experience with online learning.

Overall Impressions

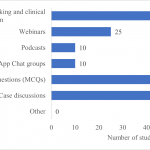

Equal numbers of both sexes were satisfied with online teaching (71.6%, n= 48; Male, 24; Female, 24), and thought that the clerkship’s learning objectives were effectively accomplished. However 67.2% (n=45) felt that clinical competence could not be achieved using solely this method. Figure 1 illustrates the additional educational resources that students believed should be included as part of online teaching. Video demonstrations of history taking and clinical examination techniques (94%, n=63), practice multiple choice questions (83.6%, n=56), and case discussions (79.1%, n=53) were the most popular choices. Podcasts and chat groups were the least desirable (14.9%, n=10 each).

Separation of the clerkship into online and face-to-face components was predicted by most students (64.2%, n=43) to have a negative effect on their performance at the end of clerkship examination. The majority of students (82.1%, n=55) requested that the online sessions be recorded and available for future reference.

Advantages and Disadvantages of E-learning

Minimising exposure to Covid-19 was rated as the most important advantage of online teaching (17.9%, n=12). Other benefits included the ability to work at their own pace and style of learning (11.9%, n=8) and the ease of access to teaching material from anywhere (10.5%, n=7). The majority of students identified the loss of direct interaction with patients (26.9%, n=18) and the lack of privacy at home (19.4%, n=13) to be major disadvantages (Table 1), and most (77.6%, n=52) preferred that their cameras were turned off during sessions.

Table 1. Disadvantages of e-learning

| Disadvantages | Number of students |

| Social isolation | 5 |

| Poor internet connectivity | 8 |

| Requires self-discipline | 8 |

| Lack of direct interaction with patients (clinical evaluation and practical procedures) |

18 |

| Lack of privacy at home | 13 |

| Other | 1 |

Anxiety

The majority of students (76.1%, n=51) reported feelings of anxiety related to the pandemic and its effects on their medical training. Anxiety levels were rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 3 (0- no anxiety, 1- mild anxiety, 2- moderate anxiety, 3- severe anxiety). The mean anxiety score was 1.4 (SD 1), with similar mean scores noted between the sexes (Male, 1.4; Female, 1.5).

DISCUSSION

The Covid-19 pandemic has dramatically transformed the practice of business, health and education globally. Although medical education has traditionally used face-to-face methods, e-learning has now rapidly been incorporated into the armamentarium of curriculum delivery. Online resources for medical education in the pre-pandemic era were generally underutilised. Our survey indicated that although all students were familiar with online learning systems, less than half used this resource prior to the pandemic. Similar findings have been reported in two other recent studies with 65-68% of medical students having no previous exposure to online teaching. 12,13 The underutilisation of this resource and the constraints imposed on undergraduate medical teaching due to the pandemic represents an opportunity to expand and improve educational techniques.

Advantages and Disadvantages of E-learning

There are several well-established advantages and disadvantages of online education specifically relevant to medical training. Some benefits include reduction in travel time and costs, increased flexibility, and convenience. Students viewed eliminating their exposure to Covid-19 in the hospital as the main advantage to online teaching. In light of limited personal protective equipment (PPE) and weak safety protocols in the public hospitals in the early stages of the pandemic, it was not surprising that students were very concerned about their personal safety. 14 In contrast, in a cross-sectional study by Dost et al; 18.63% of United Kingdom (UK) medical students identified self-paced learning as the main advantage. 9 As part of a competency-based medical education system, self-paced learning removes time pressures and can increase retention. 15 UK students were able to view on-demand recorded classes which facilitated self-paced learning and may partly explain the difference found in our survey. Students at The UWI did not have the benefit of this facility, although over 80% wanted it implemented in future improvements.

E-learning is not without some disadvantages, and undergraduate Orthopaedics is a skills-oriented craft requiring both knowledge and technical skills in physical examination and surgical techniques for clinical competence. Similar to the study by Baczek et al; our students felt that the largest limitation to online teaching was the absence of direct patient interaction and the lost opportunity to develop clinical skills. 9 It is therefore not surprising that online activities which focused on clinical practice, such as videos that demonstrated history-taking and physical examination techniques, were highly valued by our students. E-learning in its current format does not allow for interaction with patients although the development of virtual patients and the simulation of a clinical scenario may offer a solution. 16

Lack of privacy at home was the second commonest disadvantage to e-learning, reported by almost 20% of our students. In a survey of UK medical students, family distraction was reported as the main barrier to effective online teaching. 9 For e-learning to be effective, the home environment needs to be conducive to knowledge acquisition.

Usage of Cameras

There is much division between students and educators on the subject of camera use during synchronous online teaching. Students are often reluctant to leave their cameras on despite evidence that it promotes greater engagement, encourages interaction, and provides more opportunities for collaborative learning. 17,18 For teachers, seeing the students’ faces permits nonverbal communication, allowing them to evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching in real-time which contributes to a more positive experience and overall satisfaction. 17,19 A survey by Castelli and Sarvary of 276 biology students revealed that 90% had their cameras off at some point during teaching. 17 The most common reasons were concern over personal appearance (41%), concern about other people being seen in the background (26%), and concerns about their physical location being seen in the background (17%). 17

More than three-quarters (77.6%, n=52) of our students preferred to have their cameras off during online teaching sessions. A similar finding was reported by Palmer et al. from a survey of medical students from The UWI in Mona, Jamaica, following the online delivery of their Orthopaedics clerkship at the start of the pandemic. 20 The inability to access a private space at home was reported by 19.4% (n= 13) of our students as the second most common disadvantage to e-learning. The lack of privacy increases the chance that family members may inadvertently appear in the background, which could have contributed to the finding that most students in our survey chose to leave their cameras off during teaching. Given the benefits of having the camera on during teaching, we recommend that teachers adopt a student-centred approach. Camera use should be encouraged but not mandated as the classroom norm, and alternatives for engagement provided to allow students to feel included and to participate in discussions.

Anxiety

Medical students are at risk of developing anxiety disorders at significantly greater rates than the general population. 21-23 Anxiety can contribute to several negative effects including poor academic performance, depression and diminished empathy towards patients. 21,24,25 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported a 28% prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the pandemic. 21 Our smaller survey found a much higher prevalence of low-level anxiety (76.1%, n=51) in final medical students of The UWI. This may be explained by several reasons. Firstly, medical students have a wider knowledge of the pandemic and the consequences of viral infection than the general population. This combined with the lack of PPE could contribute to an increase in anxiety and is consistent with their concern about safety being the main benefit to online education. Secondly, there are significant psychological consequences to the rapid changes in curriculum delivery, and online education itself has been shown to increase anxiety levels in medical students. 21,25,26 Thirdly, academic-related factors are noted to contribute to high baseline levels of anxiety in medical students. Most of our students believed that there would be a negative effect on their academic performance due to the absence of patient contact which was noted to be the biggest disadvantage of online education. This could further exacerbate their anxiety.

The novel nature of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in much fear and uncertainty amongst the general population, and therefore it is important to provide additional support for medical students who are already at risk of depression and anxiety.

Satisfaction with E-Learning

Our study found a high level of satisfaction with e-Learning, with the majority of students believing that it effectively increased their knowledge through well-defined learning objectives. Wide acceptance and overall satisfaction with e-learning have also been reported by several other studies, including one from the Mona campus of The UWI. 4,8,20

Two-thirds of our students acknowledged that competence as a doctor could not be accomplished using only online teaching. Several recent publications have concurred that online teaching cannot totally replace face-to-face teaching of clinical skills. In the study of UK students, 82% believed that they could not learn practical clinical skills through online teaching [9]. 9 Olmes et al. found that 76% of medical students in a German university did not believe that an online course could replace direct patient contact in the hospital. 27

Although there is tremendous satisfaction and acceptance of online teaching and learning programmes, it is clear that the clinical practice of medicine requires a high degree of direct patient interaction.

The UWI is a multi-campus regional institution with medical schools located on four islands. Traditionally, differences in teaching curricula have been cited as one of the reasons that the performance of students varies widely across sites. The expansion of e-learning caused by the pandemic provides a unique opportunity to harmonise medical education at The UWI. Benefits include cost-effectiveness, the ability to deliver synchronous uniform educational material and greater collaboration among staff and students.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The percentage of students who completed the online questionnaire was low which may negatively affect the generalisability of our study’s results. Additionally, since participation was voluntary, it is possible that the students who responded to the survey request are also the ones most likely to engage in online education, introducing potential selection bias. Finally, although all questionnaires were anonymous, students may have been inclined to respond more favourably since the survey was being conducted by their teachers and the university.

CONCLUSION

Restricted face-to-face interactions during the pandemic have radically transformed medical education. Both students and teachers recognise that the versatility and flexibility of e-learning is well-suited for the varied learning styles of students, and should remain incorporated in curricula post-pandemic. However, the inherent limitations of e-learning implies that it cannot completely replace face-to-face clinical exposure in producing competent, safe doctors.

Blended learning programmes which combine face-to-face instruction with e-learning, have been shown to be both highly effective and to enhance learner success and satisfaction. 28 Our findings suggest that medical students are receptive to e-learning but require the clinical exposure of blended learning to achieve professional competence.

Acknowledgements: Shelly Ann Hunte provided technical support for the online survey.

Conflict of Interest: The Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Ethics Approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the Campus Research Ethics Committee, Graduate Studies and Research, The University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, Trinidad (CREC-SA.0511/09/2020).

Informed Consent: All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Funding: None

Authors Contributions: Both authors were involved in the design of the study, administration of the survey, data collection and analysis, and preparation and approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ. The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus. 2020.

- Kogan M, Klein SE, Hannon CP, Nolte MT. Orthopaedic education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2020 Jun 1.

- Stambough JB, Curtin BM, Gililland JM, Guild III GN, Kain MS, Karas V, Keeney JA, Plancher KD, Moskal JT. The past, present, and future of orthopedic education: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2020 Jul 1;35(7):S60-4.

- MacDonald DRW, Neilly DW, McMillan TE, Stevenson IM, SCORE Collaborators, and On behalf of the SCottish Orthopaedic Research collaborativE (SCORE) @SCOREortho. Virtual orthopaedic teaching during COVID-19: Zooming around Scotland. The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 2021 103:1, 44-49. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsbull.2021.12 (Accessed 29/10/2021).

- Chang DG, Park JB, Baek GH, Kim HJ, Bosco A, Hey HW, Lee CK. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on orthopaedic resident education: a nationwide survey study in South Korea. International Orthopaedics. 2020 Nov;44(11):2203-10.

- Figueroa F, Figueroa D, Calvo-Mena R, Narvaez F, Medina N, Prieto J. Orthopedic surgery residents’ perception of online education in their programs during the COVID-19 pandemic: should it be maintained after the crisis? Acta Orthopaedica. 2020 Sep 2;91(5):543-6.

- Bączek M, Zagańczyk-Bączek M, Szpringer M, Jaroszyński A, Wożakowska-Kapłon B. Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study of Polish medical students. 2021 Feb 19;100(7).

- Warnecke E, Pearson S. Medical students’ perceptions of using e-learning to enhance the acquisition of consulting skills. The Australasian Medical Journal. 2011;4(6):300.

- Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al-Nusair L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. British Medical Journal (open). 2020 Nov 1;10(11): e042378.

- Blunsdon B, Reed K, McNeil N, McEachern S. Experiential learning in social science theory: An investigation of the relationship between student enjoyment and learning. Higher Education Research & Development. 2003 May 1;22(1):43-56.

- Chastonay P, Brenner E, Peel S, Guilbert JJ. The need for more efficacy and relevance in medical education. Medical Education. 1996 Jul;30(4):235-8.

- Khan AM, Patra S, Gupta P, Sharma AK, Jain AK. Rapid transition to online teaching program during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from a medical college of India. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2021;10.

- Singh K, Srivastav S, Bhardwaj A, Dixit A, Misra S. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single institution experience. Indian Pediatrics. 2020 Jul;57(7):678-9.

- Boodram K. Nurses worry over PPE as cases rise. Trinidad Express. August 18, 2020. https://trinidadexpress.com/news/local/nurses-worry-over-ppe-as-cases-rise/article_3582b20e-e1b9-11ea-86c2-8fa65285dcd3.html (Accessed 28/11/2021).

- Tullis JG, Benjamin AS. On the effectiveness of self-paced learning. Journal of memory and language. 2011 Feb 1;64(2):109-18.

- Minh DN, Huy TP, Hoang DN, Thieu MQ. COVID-19: Experience from Vietnam Medical Students. International Journal of Medical Students. 2020 Apr 30;8(1):62-3.

- Castelli FR, Sarvary MA. Why students do not turn on their video cameras during online classes and an equitable and inclusive plan to encourage them to do so. Ecology and Evolution. 2021 Apr;11(8):3565-76.

- Racheva V. Social aspects of synchronous virtual learning environments. In AIP Conference Proceedings 2018 Dec 10 (Vol. 2048, No. 1, p. 020032). AIP Publishing LLC.

- Mottet TP. Interactive television instructors’ perceptions of students’ nonverbal responsiveness and their influence on distance teaching. Communication Education. 2000 Apr 1;49(2):146-64.

- Palmer W, Christmas M. Conversion to Online Teaching of a Clinical Clerkship during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Caribbean Medical Journal. https://www.caribbeanmedicaljournal.org/2020/12/12/conversion-to-online-teaching-of-a-clinical-clerkship-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (Accessed 29/10/2021).

- Lasheras I, Gracia-García P, Lipnicki DM, Bueno-Notivol J, López-Antón R, De La Cámara C, Lobo A, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(18):6603.

- Tian-Ci Quek T, Tam WS, X Tran B, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Su-Hui Ho C, Chun-Man Ho R. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019 Jan;16(15):2735.

- Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, Wang X. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Medical Education. 2019 Dec;19(1):1-3.

- Hu KS, Chibnall JT, Slavin SJ. Maladaptive perfectionism, impostorism, and cognitive distortions: Threats to the mental health of pre-clinical medical students. Academic Psychiatry. 2019 Aug;43(4):381-5.

- Thomas DL, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Academic Medicine. 2006;81(4):354-73.

- Frajerman A, Morvan Y, Krebs MO, Gorwood P, Chaumette B. Burnout in medical students before residency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;55:36-42.

- Olmes GL, Zimmermann JS, Stotz L, Takacs FZ, Hamza A, Radosa MP, Findeklee S, Solomayer EF, Radosa JC. Students’ attitudes toward digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey conducted following an online course in gynecology and obstetrics. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2021 Oct;304(4):957-63.

- Dziuban, C., Graham, C.R., Moskal, P.D. et al. Blended learning: the new normal and emerging technologies. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 15, 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0087-5 (Accessed 29/10/2021).

Appendix 1. Questionnaire for Opinions and Attitudes of Medical Students towards Online Teaching of the Orthopaedics Clerkship during Covid-19

- How old are you?

- What is your sex?

Male Female

- Have you ever used The UWI My eLearning or any other online Learning Management System for online education before the pandemic?

Yes No

- In your opinion what are the main advantages of online teaching? (Select all that apply)

- Ease of access from anywhere

- Ability to remain at home

- Access to online lectures

- Fairness (all students receive the same educational material)

- Ability to learn at your own pace and style

- No exposure to Covid-19

- In your opinion what are the main disadvantages of online teaching? (Select all that apply)

- Social isolation

- Poor internet connectivity

- Requires self-discipline

- Lack of direct interaction with patients (clinical evaluation and practical procedures)

- Lack of privacy at home

- Other, please list

- Which of the following should be included as part of on-line teaching? (Select all that apply)

- Video demonstration of history-taking and clinical examination techniques

- Webinars

- Podcasts

- WhatsApp Chat groups

- Practice multiple choice questions (MCQs)

- Case discussions

- Other, please list

- How would you rate your level of anxiety during the pandemic?

1 No anxiety 2 Minimal Anxiety 3 Neutral 4 Moderate Anxiety 5 Severe Anxiety

- The cameras of both lecturers and students should be left on during the teaching session.

Yes No Don’t know/Unsure

- All teaching sessions should be recorded and available for future reference.

Yes No Don’t know/Unsure

- How effective is the current online teaching in terms of achieving the learning objectives of the Clerkship?

1 Very ineffective 2 Moderately ineffective 3 Neutral 4 Moderately Effective 5 Very Effective

- How do you believe the separation of the clerkship into an online component and a face-to-face component will affect your performance at the end-of-clerkship examination?

1 Very negative effect 2 Moderately negative effect 3 No effect 4 Moderately positive effect 5 Very positive effect

- Please rate your overall satisfaction with online teaching.

1 Very dissatisfied 2 Dissatisfied 3 Unsure 4 Satisfied 5 Very satisfied

- Competence as a doctor can be achieved using only online teaching methods.

Yes No Don’t know/Unsure